Absinthe.se

The premier independent absinthe resource since 2003

The history of absinthe

So many stories, myths and rumours are heard and told about absinthe. The question is how much truth lies in it. To get to the bottom of that we need to go more than 200 years back in time and travel to the Jura mountains in Switzerland and France where absinthe as we know it started its journey.

Generally when we think or speak of absinthe, we think of the glittering Parisian theatres, the Moulin Rouge, the artists, the cafés and all the icons of the Belle Epoque.

However, its origin is far more subtle than that. Absinthe was first produced near Couvet in Switzerland, and nearby Pontarlier in the Doubs region of France. To many this rural part of France is still considered the home of absinthe.

Dr. Pierre Ordinaire - the medicine man

Supposedly it was Dr. Pierre Ordinaire who invented absinthe in 1792. It was shortly after the French revolution that he produced the first commercial absinthe, or more accurately it was actually a medicine, meant to cure just about anything. It was recommended for the treatment of epilepsy, gout, kidney stones, colic, headaches and worms.

Dr Ordinaire travelled the countryside with his medicine and sold it as a cure-all to the people there. The medicine included typical herbs for the region as well as other herbs known for their medicinal properties. Local wormwood, roman wormwood, fennel and several other ingredients made up the first version of what was to become France's most popular drink.

Another man, Major Henri Daniel Dubied was very interested in the invention by Dr. Ordinaire. Not as a medicine but rather as an aperitif. The recipe had changed slightly and the previously medicinal concoction had instead become quite potable and people started to like it, not only for its supposed medicinal qualities. Dubied allegedly purchased what was reputed to be Ordinaire’s original formula from two sisters named Henriod at the beginning of the 19th century and started a larger scale production. Their distillery was located in the little town of Couvet in Val-de-Travers, Switzerland.

Pernod Fils and the establishing in France

French demand for the new drink from Couvet across the border in Switzerland - absinthe - became so great that a factory was built in Pontarlier, France and started production there in 1805. This eliminated previous problems with taxes and trade between the two countries. The company was run by Dubied's son-in-law, Henri-Louis Pernod. It was to become one of the largest and most successful companies in France. Little did they know that the Pernod Absinthe would be such a success that others would try to copy not only the drink and the recipe but also the name.

Pernod Fils distillery in Pontarlier, France

Absinthe's popularity increase

The French troop fighting in Algeria in the 1840's used absinthe as a fever preventative, and upon their return to France, they brought the taste for absinthe with them. It became an instant success. The bars and bistros where crowded by people drinking absinthe, and every day at around 5 pm. it was "l'Heure Verte" - the Green Hour.

Of course, since absinthe was such a success, and so was the Pernod company, more wanted a piece of it all. There was a multitude of brands that more or less copied the name Pernod, and many of them became truly successful as well.

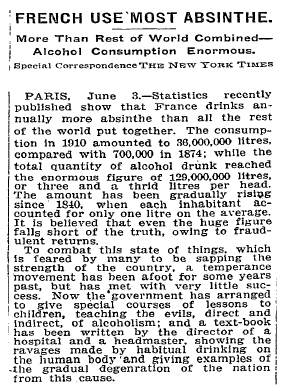

New York Times June 11, 1911

Absinthe hit its peak during the years from 1880-1910. It was a quintessential part of Belle Epoque French society. The French consumed far more absinthe than any other country, and absinthe drinking was one of the special marks of Paris in the 1890s and early 1900’s. Absinthe was a symbol of inspiration and daring, and became indelibly associated with the bohemian artists and writers who were revolutionising art and literature. Many famous works of art were directly inspired by the drink, including some of Degas’ and Van Gogh greatest masterpieces, and the very first cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque.

Everyone drank absinthe – society ladies, gentlemen-about-town, businessmen and politicians, artists, musicians, ordinary working-men. In 1874 alone, France consumed 700,000 litres of absinthe, but by 1910, this figure had exploded to 36,000,000 litres of absinthe per year. That sounds like a whole lot, but it actually accounted for only 3% of the total french alcohol consumption, whilst wine had 72% of the total. The french drank a lot!

What is important to keep in mind though is that the majority of the binge-drinking of absinthe took place in the larger cultural capitols of France such as Paris and Marseille for example. In the countryside absinthe was just another drink you quietly enjoyed like any other drink be it wine or brandy.

It was also in the major cities that the problems with adulterated cheaper artificial absinthes emerged. Companies with little scruples but with a hunger for profit saw their chance to produce cheaper absinthes to the lower classes of society. Much of absinthes trouble to come was due to these faux products and of course the rising problem of a steadily increasing consumption of alcohol in general.

The war on absinthe

Leading up to the ban of absinthe in several - but certainly not all - countries in the world was a series of incidents and a whole lot of lobbying from the Anti-alcohol-league as well as the wine industry.

Seeing how the French people drank more and more much was done to prevent this and absinthe was hit hardest. Being a high-proof spirit and, at least in the major cities, fairly cheap it was the perfect target.

On the one side there was the anti-alcohol-league providing scientific studies that proved absinthe to be a terrible poison. On the other side was their opponents providing studies contradicting those "findings". One of the most well known, and cited, scientists in this field was Dr. Magnan. He made several studies on the effect of absinthe. Reading them today they're really not that scientific and would be heavily questioned, but at the time it made out the creme-de-la-creme of studies.

He did find a component in absinthe which was previously unknown, the so called active ingredient of wormwood - Thujone. His studies on the effects of thujone was used to ban absinthe.

Thujone is a terpene and is related to menthol, which of course is known for its healing and restorative qualities. Thujone is a naturally occurring substance in wormwood and is also found in the bark of the Thuja, or white cedar and in other herbs besides wormwood - including tansy and the common sage used in cooking. Aside from absinthe, other popular liquors, including Chartreuse and Benedictine, also contain small amounts of thujone.

Dr. Magnans studies proved that thujone was indeed a poison, and giving a laboratory rat a certain amount of ordinary drinking alcohol and then later the same amount of concentrated thujone oil - which killed the animal - he "proved" that since absinthe contained thujone and thujone killed the rat, absinthe was a poison. Not taking into account of course the actual levels of thujone found in absinthe, which are well below the lethal dose for humans.

Further "proving" the dangers of absinthe due to its containing thujone he stated absinthe to contain around 250-260 mg/kg of thujone. The numbers were mere calculations based on the amount of wormwood used in a standard absinthe recipe and the amount of thujone found in wormwood. Again, not taking into account that not all of this follow in the distillation of absinthe, which makes the actual level of thujone found in the finished drink much lower. However, not even the 250mg/kg would actually kill a man drinking that absinthe.

Extremely high doses of thujone are however dangerous, and have been shown to cause convulsions in laboratory animals, but the concentration of thujone actually found in absinthe is many thousands of times lower than this. Thujone's mechanism of action on the brain is not fully understood although certain structural similarities between thujone and Tetrahydrocannabinol (the active component in marijuana) have led some to hypothesize that both substances have the same site of action in the brain. More recent scientific research however has completely discredited this idea. More important, thujone is rather irrelevant to absinthe itself.

Read more on thujone, the effects of thujone and a number of scientific studies on the subject here, on thujone.info.

The ban of absinthe

Absinthe was originally fairly expensive, and largely a drink of the upper-middle classes. However, by the second half of the nineteenth century it had fallen dramatically in price, both because of increasing economies of scale in its production, and because most producers had switched from grape alcohol to far cheaper grain and beet alcohols. At the same time the number of brands exploded, with many catering for the very cheapest end of the market.

Absinthe became increasingly popular amongst all classes of French society, and began to displace wine as the standard drink of the French working class. During this period the French wine industry was struggling with the crippling effects of both oidium (a kind of mildew) and phyloxera (an incurable beetle infestation deadly to vines). Almost all the French national vineyard had to be replanted, a process that took decades and resulted in a prolonged shortage of wine, and a consequent rise in wine prices. Increasingly, absinthe was the affordable, and far more alcoholic, alternative to wine. This was both a major reason for its enormous popularity, and ultimately the root cause of its downfall. When the wine industry began to recover in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the politically well-connected grape growers, seeking to recover the market share they had lost, began to agitate for the prohibition of what they termed "unnatural" products like absinthe.

In the 1880's, there was for the first time concern about the results of chronic abuse of absinthe. Chronic use of absinthe was believed to produce a syndrome, called absinthism, which was characterized by addiction, hyper excitability, and hallucinations. The science, or pseudo-science behind these reports was dubious and often obviously flawed – but the reports were published in the popular press of the day and widely believed. It is now thought that the symptoms of "absinthism" were due primarily to the effects of the alcohol itself, and also perhaps to the many sometimes extremely dangerous chemical adulterants used in cheap absinthes of the time. Well-made absinthes used chlorophylic colouration from herbs to achieve their characteristic green colour. This however was an expensive and difficult to control process, so unscrupulous low cost producers substituted chemicals such as copper sulphate to achieve the same effect. Antimony chloride – another highly poisonous substance - was also used to help the drink become cloudy when added to water.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries France, together with many western countries, was under pressure from various temperance movements and their constituents to curb alcohol consumption on a governmental level as it was seen to morally corrupt its citizens. In the midst of this prohibitionist excitement, the word "absinthism" came to lose its specific meaning. Absinthism and alcoholism were confused, and an alcoholic was simply deemed an "absinthe drinker". This confusion of meaning seems to have been deliberately encouraged by the prohibitionist movement. Wine was believed to be healthy and natural, since it came from the land and was a time-honored tradition, not to mention a major source of revenue. Absinthe, however, was made with industrial alcohol, and was moreover by far the most alcoholic of all liquors. It’s not surprising, that by the 1890's, absinthe had become the primary target for the French temperance movement.

This narrow focus on absinthe was of course entirely in the interests of the powerful wine industry lobby. After all, under the growing threat of Prohibition, how better to draw attention away from your own alcoholic product –wine - than to make people believe that it is the healthy, natural exception to the "bad" rule? Adding to the political agitation against absinthe was its popularity not just with the working class, but also with the radical bohemian set – young artists like Van Gogh and Toulouse Lautrec, writers like Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine, to name just a few. Their scandalous lifestyles and debauched behaviour shocked and outraged the establishment, and absinthe, their favourite drink, came to encapsulate in the public mind everything that had gone wrong with conservative France.

Like a vice slowly tightening, the pressure to ban absinthe inexorably increased. The last straw was a series of particularly brutal family murders which were – largely unfairly – blamed on absinthe consumption. The most notorious of these was the celebrated Lanfray case mentioned above, which riveted the European press in 1905.

The absinthe murders

It is quite a long story to tell, but to keep it simple, it goes something like this; It was a man named Lanfray. He killed his entire family with a shotgun, his wife who was four months pregnant and his four year old daughter. He tried to take his own life, but failed.

Since he was quite the drinker, it was said that it was absinthe that drove him to commit this hideous crime. No one took any notice to the fact that Lanfray during that day had more alcohol than anyone would consider healthy. And not only absinthe. Absinthe actually accounted only for a very small part of it all.

In the morning he started off with two absinthes, before he went to work. On the way there, he, his father and his brother stopped at a café where he had a Crème de menthe and a Cognac. At lunch break at his work in the vineyards, he had no less than six glasses of "Piquette", a heady local wine. In the afternoon, just before he ended work, he had another glass of wine.

At their way back from work, they again stopped at a café, and had a cup of coffee laced with brandy. In the evening Lanfray and his father each had another liter of "Piquette". And that wasn't enough. Lanfray poured himself some coffee and laced it with his own powerful homemade brandy.

He got into an argument with his wife and asked her to polish his shoes for him. When she refused Lanfray went to get his rifle and shot her once in the head, killing her instantly. His father fled and his four year old daughter, Rose, heard the noise and entered the room. He then shot Rose and her two year old sister. He shot himself in the jaw and was arrested by police which had been notified by Lanfray's father.

After recovering from his selfinflicted injury he was put on trial for the murders of his own family. His attorneys argued that it was the two ounces of absinthe he had consumed before that was to blame for his actions. A leading Swiss psycholigist, Dr. Alber Mahaim also testified that Jean Lanfray suffered from a "classic case of absinthe madness".

However, prosecuter Alfred Obrist, argued that the two ounces of absinthe he had ingested were minor in relation to the large amounts of other alcoholic beverages he had consumed during that day.

Aftermath of the murders

Public reaction to the case was extraordinary, and it focused on just one detail – the two glasses of absinthe he had drunk beforehand. Forgotten was the fact that Lanfray was a thoroughgoing alcoholic who habitually drank up to 5 litres of wine a day. Forgotten also, was that on the day of the attack he had consumed not only the two absinthes before going to work – hours before the tragedy – but also a Crème de menthe, a cognac, six glasses of wine to help his lunch down, another glass of wine before leaving work, a cup of coffee with brandy in it, an entire litre of wine on getting home, and then another coffee with Marc in it. People were in no doubt. It must have been the absinthe that did it. Within weeks, a petition demanding that absinthe be banned in Switzerland was signed by over 82 000 local people. The momentum to ban the drink was now unstoppable. Only three months after the trial, in May 1906 the Vaud legislature voted to ban absinthe. Eventually, effective by October 7, 1910 the production, posession and sale of absinthe was banned in all of Switzerland.

Additionally, absinthe was banned in Belgium in 1905, in the USA in 1912 and finally in France – distracted and shell-shocked by the first defeats of World War I - in 1915. In the end this magical and historic elixir that had once captivated, delighted and inspired a nation, went out not with a bang, but with the merest whimper. Most of the great absinthe-producing firms went bankrupt, or amalgamated, or switched to producing pastis. Some firms transferred their production to Spain, where absinthe was never banned, and where it continues to be made on a small scale. In the Val de Travers region of Switzerland, production went underground, and large scale bootlegging operations existed all the way up to its relegalization on March 1, 2005 when many of the bootleggers simply applied for a distillery permit and got one. In many countries though absinthe was never formally prohibited – it just faded from sight.

Absinthe has never been banned in the UK, Sweden or Denmark nor in much of Southern and Eastern Europe like Spain or Portugal for example.

Absinthe after 1915

Some producers opened up distilleries or hired distilleries across the border to Spain to continue producing absinthe there, as it was never banned there. Some of these include Edouard Pernod and Pernod Fils. The two eventually merged and Pernod absinthe, although the recipe changed slightly over time, was continually produced in Tarragona all the way up to around 1965.

Many Spanish distilleries also made their own absinthe, or Absenta in Spanish, and had done so since the peak of absinthe in the late 1800's. Several of these continued to do so well into the 70's and 80's. Sadly they turned to cheaper methods to manufacture their absinthes as time passed and very few of the Spanish absentas made after the 1970's are actually any good. Still today there are a lot of Spanish absinthe available on the market, however only one - Obsello Absenta - is even close to the finer old Spanish Absentas such as Escat, pre 1970 Montana, Argenti etc.

The stock that was left in France at the time of the ban in 1915 was allowed to be sold off and much of it was exported. Eventually the government bought up large stocks and actually used it to manufacture explosives for the war.

Written by Markus Hartsmar

- absinthe books and poetry -

Many writers "of old" wrote poems or passages about absinthe. Some drank it, some didn't. Find some of them here as well as reviews and notes on modern books about absinthe.

- latest news and additions -

The Absinthe Poetry section has seen several updates the past days. Poems and information about more authors; Antonin Artaud, Arthur Symons, Francis Saltus Saltus, Florence Folsom and Robert Loveman. Open your mind and have a drink while you enjoy their lyrics.

Read more...

- absinthe.se on facebook -

It's the new bistro, the new bar in town. A good place to meet when meeting in real life isn't always an option. Meet me on facebook for more updates from the absinthe world.